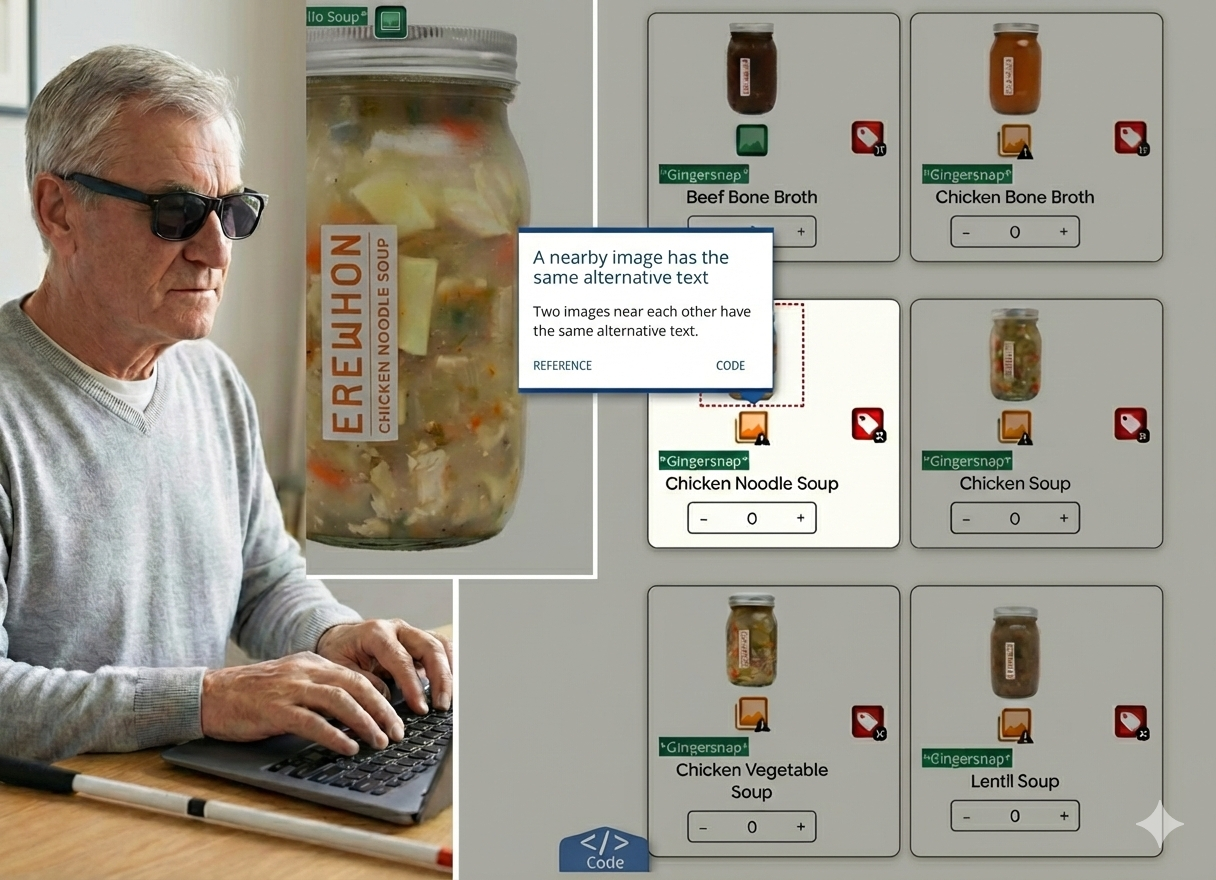

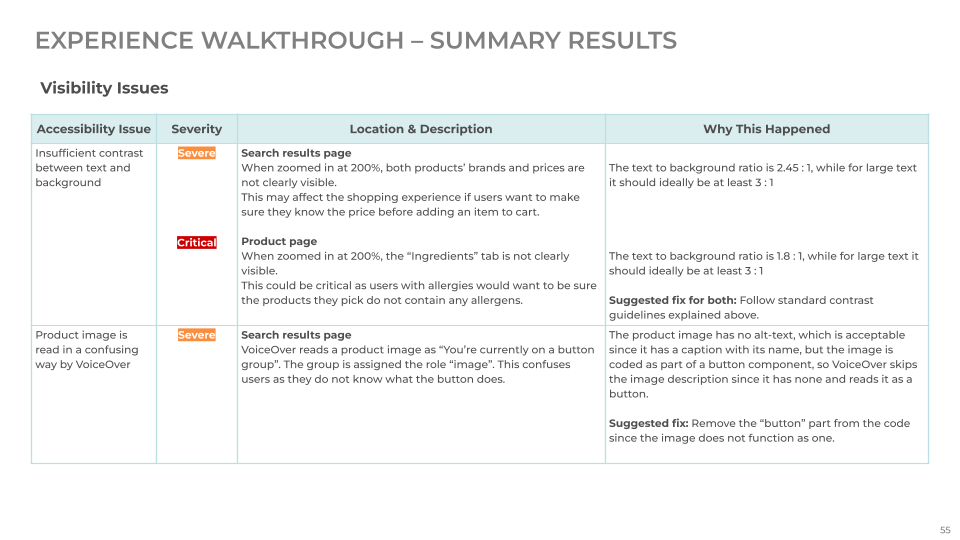

Left: Persona simulation. Right: Persistent accessibility errors verified in the current site redesign.

Uncovering Silent Barriers at Erewhon

An accessibility audit to dismantle digital exclusion

Role: UX and Accessibility Specialist

Methods: Automated and manual inspections | Experience walkthrough

Tools & References: SortSite, WAVE, WCAG2.1

Executive Summary

Challenge

The Erewhon website exhibits several critical accessibility issues that affect users with mobility and visual impairments.

Key Findings

Keyboard Traps: Search filters and "Ingredients" tabs are unreachable without a mouse.

Silent Navigation: VoiceOver fails to announce the hamburger menu or cart updates.

Blocked Purchase: Quantity steppers and cart counts are invisible to screen readers.

Recommendations

To address these issues, the site’s code should be reviewed for proper semantic structure. This includes implementing ARIA roles, labels, and descriptive markup to clarify component functionality. Additionally, all interactive elements in the shopping flow should be made keyboard-focusable.

Scope

Home Page • Search Results • Product Detail Page

Methodology

I evaluated the Erewhon digital experience against WCAG 2.1 Level AA standards. While technical compliance was the baseline, the goal was to identify barriers across the four foundational principles (Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, Robust). To ensure a comprehensive audit, I utilized a triangulated approach as follows:

Automated Code Inspection

Automated tools are the first line of defense for catching structural syntax errors.

The Goal: Rapidly identify non-conformance issues like broken heading hierarchies and missing alt text.

The Tools: Leveraged SortSite for site-wide code scanning and WAVE to visualize structural gaps in the DOM.

Manual Code Inspection

Since automated tools catch only about 30% of errors, manual review is critical for validating behavior.

The Goal: Uncover interactive barriers that code scanners miss, such as trapped focus states or illogical tab orders.

The Tools: Conducted deep-dive audits using VoiceOver (iOS) and Keyboard-only navigation to simulate the assistive technology experience.

Experience Walkthrough

Compliance does not always equal usability. This step tested the actual "shopping friction."

The Goal: Measure the cumulative impact of small bugs on a user’s ability to complete a purchase.

The Process: Simulated core user journeys, including Search, Add to Cart, and Checkout, to identify friction points that block task completion.

Key Findings

The triangulation of automated and manual testing revealed a consistent pattern: while the visual interface is refined, the underlying code structure creates critical barriers for assistive technology users. The audit identified two primary themes of exclusion:

Raw data from the experience walkthrough revealing a pattern of missing labels on interactive elements.

Theme 1

The "Silent" Storefront (Semantic Gaps)

The Issue: Key interactive elements, including product images and status indicators, lack semantic labels.

The Impact: Screen reader users are navigating in the dark. Without descriptive tags, the "Add" button is just an unread graphic, and the "Cart" status is invisible, making it impossible to confirm a purchase.

Specific Evidence:

The [+] icon on search results is unannounced.

Product images are decorative but occupy focus, creating noise without value.

The Ingredients Tab is skipped entirely by VoiceOver.

Theme 2

The Navigation Dead-End (Keyboard Traps)

The Issue: Critical touchpoints are coded as static elements rather than interactive buttons.

The Impact: Keyboard-only users face a "digital wall." They can see the path to purchase but cannot physically enter it because the focus state skips essential controls.

Specific Evidence:

The Hamburger Menu and Search Filters are unfocusable.

The Quantity Stepper cannot be adjusted via keyboard.

The "Add to Cart" button has a broken focus target (text only), causing activation errors.

Recommended Action

Phase 1

Technical Remediation

Prioritizing high-impact updates to unblock essential shopping tasks.

Refactor Static Controls: Convert non-semantic elements (like the Hamburger Menu and Search Filters) into true

<button>elements to immediately restore keyboard focus.Clarify Context: Add

aria-labelsto icon-only buttons (like "Add to Cart") and status indicators so screen reader users receive clear feedback on their actions.

Phase 2

Process & Validation

Ensuring stability and deepening insight beyond the code.

Inclusive User Testing: Move beyond automated audits by conducting sessions with users who have diverse disabilities to catch real-world friction.

QA Guardrails: Establish specific accessibility checks in the development workflow to prevent semantic gaps from slipping back into future updates.

Retrospective

While the automated tools provided data, the manual walkthroughs provided truth.

This audit challenged me to look beyond the "happy path" and confront the real-world friction that excludes users. It was a powerful reminder that accessibility cannot be an afterthought; it must be the foundation of any interface that claims to be intuitive.

Next Project

Washington Post: Cultivating Gen Z Loyalty

Turning childhood memories into lifelong relationships